Otis Mountain Get Down: Little Mountain, Big Heart - Part One

Published in Offprint Magazine // September 4, 2015

To find it, you almost have to know it’s there. Roaming State Highway 9N, you could easily cruise by Lobdell Lane without looking twice. Yet, tucked in a low-elevation pocket of the Northern Adirondacks, in the southern portion of New York’s Champlain Valley, there exists a place where music mingles in the pine trees, where campfire smoke curls high over a circle of friends.

On the second weekend of September, turning down that dirt lane will deliver you to a three-day music festival that defies stereotypes and exceeds expectations. You’ve arrived at Otis Mountain Get Down, and you’re going to have a weekend for the ages.

Located in Elizabethtown, NY—population 1,163 as of the 2010 U.S. census [1]—Otis Mountain is in the thick of Adirondack country. But, with a gradual approach to the clearing and a gentle ski-hill slope rising above the festival grounds, the terrain is welcoming, not imposing.

Terrain surrounding Elizabethtown, NY

OMGD features over thirty acts in a variety of genres, from whiskey-infused bluegrass and old-time country, to righteous soul and funk, to modern hip-hop and electro. The goal is not to showcase major national bands or attract corporate sponsorship. Standing out from— and in many ways against— the “festival culture” that defines well-known events like Coachella and Bonnaroo, OMGD instead offers an intimate, interactive, and affordable weekend experience in the woods.

In part one of a two article series, Offprint takes a look at who and what have made Otis what it is today. From its days as a small community ski hill, to a six-year stint as a summer bluegrass haven, to a 21st Century music festival revival, Otis Mountain has a story to tell.

The Ski Years

The life of Otis Mountain has been one of ups and downs, with alternating years of high success and years of dim closures. Only in the last twenty of its eighty-year history has it operated continuously.

Before its transition into a public-use area, the mountain sat on private farmland owned by the Lobdell family of Elizabethtown. Starting in January 1940, the Elizabethtown Ski Club leased the property in order to operate a small ski program. The club stayed in business sporadically until 1959. Not much documentation of these early years exists.

View from the top of Otis Mountain ski hill. Courtesy Jeff Allott.

Jeremy Davis, founder of the New England Lost Ski Areas Project and noted ski historian, has researched Otis Mountain extensively. He speculates as skiing became a more popular form of recreation, bigger mountains began to attract customers, so small community hills like Otis lost support.

Otis lay dormant until local volunteers formed the new Otis Mountain Ski Corporation, opening the hill in January 1965. Yet within five years, the corporation was unable to pay operations costs. In 1970 it asked locals Jane and Herb Hildebrandt to purchase the property.

The Hildebrandts spent two years renovating and recouping money from the acquisition and repairs. The couple added a new T bar to the lift, made updates to the facilities, and added free Wednesday night skiing. The Hildebrandts kept Otis running from 1972-1979 as an affordable location for families to ski.

Getting in line at Otis ski hill. Courtesy of Jeff Alott.

Young skier at Otis Mountain. Courtesy of Jeff Allott.

It was during these years that Elizabethtown native Jeff Allott became acquainted with the mountain, and with the Hildebrandts.

“I literally grew up skiing there. I was the ski patroller at one time, I worked the hot dog stand, I did every job,” Allott remembers. “It was a vital thing, back when skiing was popular and a lot of small towns had their own ski hills. All the school ski hills would come to Otis instead of Whiteface, which was too big and expensive.”

In the season of 1979-80, there was much anticipation that the Winter Olympics in nearby Lake Placid would draw attention and bring business to Otis. But, Davis notes, “that season and the following were terrible for snowfall, it was very dry winter so the Hildebrandts weren’t able to open. They tried to get the area going again in ‘82, and there wasn’t enough snow either so that was the end of that operation.”

By this time Allott had graduated from high school and traveled the country as a ski mechanic. But he frequently returned to the mountain he grew up on. “Every year when I’d come back I’d say to Jane, ‘one day when I get my act together I’m gonna buy that and we’ll get it running again.’”

In 1994, he finally did. Having earned a degree in mechanical engineering, he started a composite materials company in Albany. When a fire took out the entire facility, he took the opportunity to relocate to Westport, about nine miles from Elizabethtown.

“That same winter of ‘94 I got a call from Jane saying ‘you have to do something someone is trying to buy the property!’” Allott recalls.

Cover of “Lost Ski Areas of the Northern Adirondacks” by Jeremy Davis

Allott was able to gather two friends and get the money together in the summer of 1995. The mountain now operates with a simple rope tow. “It’s been running ever since, and we’re coming up on our 20th year,” he says, with amazement.

Such a story of revival is quite unusual, Davis notes. “It’s a rare case that you have an area that’s been closed so long that opens on some kind of a level,” he explains. In fact, of fifty-four former ski areas of the Northern Adirondacks that Davis has documented, only seven have reopened. Otis, then, is quite the exception.

A Bluegrass Addition

Allott continued to open Otis each winter. He remembers that early in the summer of 2002, someone mused that the property would be an ideal site for a music festival.

“Surprisingly four or five of my buddies said ‘yeah I’ll help you with that.’ Literally that summer we threw a stage together, ran power up there, and focused on mountain music, just bluegrass and family friendly music,” he says.

The theme stuck. The Otis Mountain Music Festival, as it was known, ran for six years until 2008. At the time, Allott says, almost no one but locals and dyed-in-the-wool bluegrass enthusiasts attended. “I would literally cruise the parking lot and never see Vermont plates, it just could not break through to Vermont,” he laments.

Growing weary of the effort required to put on the festival, Allott and company took a hiatus for one year, then two, then three, and ultimately gave up altogether. But the ski hill lived on each winter.

A Festival Revived

It seems only fitting that a property passed from friend to friend, from person to person in the community, would ultimately end up repurposed in the hands of those who enjoyed it for so many years.

Allot raised his family in and around Westport and Elizabethtown. “The ski area had continued to grow and my kids all grew up skiing there. We went every weekend,” he remembers.

The main stage. Courtesy of Otis Mountain Get Down.

His oldest son, Zach, attended Champlain College in Burlington, VT and would frequently bring friends home to enjoy skiing and other activities at Otis. Many of those people— including Austin Garrett, Colby Sears, and Quillan George—would ultimately help him resurrect the summer festival aspect of Otis.

During Zach Allott’s college years at Champlain, he lived in a Burlington apartment— affectionately dubbed “The Range” — that housed a group of about fifteen rotating people, generally seven at a time.

“The Range,” was, according to Sears, “a big spot to go hang out, and that’s where the friendships really took off.”

“There was a bar, mini ramp, and bands just about every weekend. Through hosting all of these acts, we had a lot of connections in Burlington’s live music scene,” George describes.

In the early summer of 2013, some of the group went to New York to go cliff jumping and stopped at Otis. George recalls looking at the old bluegrass stage at the bottom of the ski hill, and saying, “Why don’t we get some bands over here?”

Fun around the fire at Otis Mountain Get Down. Courtesy photo.

Plans began the next day. “I started texting friends in bands with the idea, and people were interested. We reached out to some more buddies that we thought would want to get involved, and started making the festival happen,” George recalls.

The initial idea was to host ten bands and reach out to immediate friends, bringing in about 100-200 people.

“As soon as we put the festival online, it blew up,” George says, “There was a rush of locals that had attended the bluegrass festival in the past that were incredibly excited to see the return of music to Otis Mountain, as well as a bunch of friends and friends of friends.”

It quickly became apparent, however, that the undertaking would be much more work than expected.

“When we first started we didn’t really have a plan,” Zach Allott admits.

George adds, “We had planned a date about a month and a half away from when we first had the idea, and quickly realized we wanted to do this right and needed more time, which is how we fell on the date in early September.”

With the core group of “The Range,” plus help from Jeff Allott and additional volunteers, the 2013 inaugural OMGD was a hit. What began as an idea to bring a group of friends and a few bands together turned into a 25 act festival with over 750 attendees, according to George.

The gang’s biggest lesson from the first year was logistics. “We were organized, but only as organized as a group of 21 to 22 year olds with no experience in putting on a festival could be,” George says.

“It’s pretty humbling, and realistically we are responsible for all these people so that kind of made us grow up fast,” Zach Allott says. “In some ways,” he adds, with a laugh.

This year, a group of thirteen Otis veterans incorporated as a small business in the form of a cooperative LLC. This structure allows them to retain earnings from year to year and for all members to have equal say.

How The Get Down Gets Done

With a formal business structure, OMGD now exists as a fully bootstrapped organization. And its members work hard all year to make each September a success.

Sears says, “We go all year, sitting in group meetings. We take a week off so right after the festival, then we sit down and plan all over again.”

The Monday after the festival, the group sorts through video footage and photos to produce a recap video and begin planning a media calendar. Next on the list is “a thank you, follow up note to everyone involved, artists, security, production, etc, what they thought worked well, and how they thought we could improve for the next year,” George says, “This feedback has been a big reason why we’ve been able to continue to grow and improve each year.”

George is the Talent Buyer as well as the Marketing Director and Music Production Director. He is responsible for booking, scheduling, and coordinating all musical acts, as well as coordinating sound and lighting. He also directs all marketing efforts.

“I try to have at least half of the lineup confirmed by 6 months out, and all of it complete by three months out,” he says, “Once we hit four months is when we really start to push everything publicly. Before that a lot of what is happening is all internal.”

Bands are selected in a number of ways. Some artists send samples via email and social media. Otis team members also nominate artists they’d like to play at the festival. George also scouts talent through connections with Burlington music venues Signal Kitchen and ArtsRiot, as well as other festivals throughout the country.

“The main idea behind how we select our line up is that we never book bands based on popularity. We choose artists based on quality, diversity, and spirit,” George states.

Late night set at Otis Mountain Get Down. Courtesy photo.

Once most artists have been locked in, much of the site prep and contract work begins. Garrett and Sears are facilities coordinators. Their tasks include negotiating terms for food and merchandise vendors, organizing and scheduling volunteers, drafting contracts, and coordinating the legal and creative elements.

Sears explains, “On the back end it’s working with insurance to make sure we’re adequately covered. What I try to work on is establish and build budgets.”

When summer dawns and the festival is only three months away, the crew has someone on site almost every weekend.

“The winters are pretty brutal on the stages and structures, so there is a lot of rebuilding and clearing out more camping for the growing number of attendees,” Garrett explains.

The group does all the building and maintenance on site and by hand. Jeff Allott is always around, linking more power to stages, mowing the grounds, and offering the wisdom of experience.

One month before the gates open, the crew pushes a marketing blitz. Posters and promotional materials are sent out, social media posts occur almost daily, and radio and local press are contacted.

One week from the festival, the team is on site full time. While there are formal positions in the collaborative’s legal structure, the roles are loose, especially during those last few days before the crowd arrives. This horizontal structure is essential to the Otis ethos.

“No one does more work than anyone else. Some people are doers on the ground, some people are coordinators,” Sears says. “The only reason we have titles is because we were nominated amongst the group, and some of us have different backgrounds that make the titles more applicable.”

More Than A Mountain

With only one week left until this year’s festival opens, the crew is working to finish the remaining elements. But, they are also reflecting on what makes Otis meaningful to them and to the Elizabethtown community.

“What we wanted to do from the beginning was provide a totally different festival environment for people,” Sears says. “At the grandiose festivals it’s $200 a ticket. This is not about that. It’s about the music, and about friends.”

Garrett agrees. “Otis has become something so much more than just a mountain or a festival to me. I love being able to take people there who have never been and show them all of the cool stuff scattered around the grounds,” he explains.

For George, the point of the festival is, “to expose people to something new. There is nothing I love more than hearing someone say ‘I’ve never heard of any of these bands.’”

In terms of the crowd, Jeff Allott has been surprised to see a parking lot full of Vermont cars, unlike his festival days. “In 2013 was 90% Vermont plates and 10% local plates, the dynamic had completely flipped. I was like ‘damn!’” he laughs.

By bringing in outside tourism from Vermont and other states, OMGD has become a small economic jolt to the community of Elizabethtown. “It’s more apparent every year it’s more than a festival,” Zach Allott says. “Last year they were selling out of everything at the stores the week of, so it’s become a viable entity for the town.”

Sears says he appreciates some of the smaller moments at Otis. “Some of my favorite times are seriously just driving the hay bale truck up and down. I have driven that truck for like 12 hours a day,” he remembers. “Everybody is so stoked on that ride up the hill. That to me says we’re doing something here, people are happy and there’s this safe environment to have fun. It comes full circle.”

Lights and a packed crowd at OMGD. Courtesy photo.

Garrett attributes a lot of the festival’s success to the attitude of the attendees. “Otis attracts such a great crowd, I can’t tell you how satisfying it is on Sunday to walk through the camp sites and see that almost everyone has cleaned up after themselves. That’s what it’s all about,” he states.

To Jeff Allott, Otis also represents a generational passing of the torch. “It was really something to see it brought to life again through my son,” he says.

—

Otis Mountain is a storied property that has been given new life. The “little ski hill that could” has survived snow-starved winters, closures, changing hands, and more than a few weekends of boot-stomping music and mayhem. With the third annual Otis Mountain Get Down just one week away, the tradition and spirit of Otis lives on.

OMGD lineup 2015.

As this article goes live, Offprint heads into the woods to meet the crew and experience life at the festival. Check back in a few weeks for a recap of the music, art, and people at OMGD 2015. To buy tickets to the festival, which runs Friday September 11-Sunday September 13, visit http://www.otismountain.com/tickets/

For more information on the history of Otis Mountain and the Northern Adirondack region, visit the New England Lost Ski Areas Project (www.nelsap.org)

The Full Otis Crew

- Zach Allott, President

- Pat Dodge, Product/Merchandise

- Ryan Forde, Designer

- Joe Fortugno, Treasurer

- Colin Frost, Volunteer Coordinator

- Leanne Galletly, Secretary

- Austin Garrett, Facilities Coordinator

- Quillan George, Talent Buyer, Music Production Director, Marketing Director

- Casey Joseph, Social Media Manager

- Evan Litsios, PR / Copywriting

- Tommy Lyga, PR

- Colby Sears, Facilities Coordinator

- Bobby Sheridan, On-site operations

- Brian Somers, Vice President

- George Watts, Media Coordinator

[1] http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml

Otis Mountain Get Down: Little Mountain, Big Heart - Part Two

Published in Offprint Magazine // October 9, 2015

One month ago, Offprint published a history of Otis Mountain, an old community ski hill in Elizabethtown, NY that is now the site of one of the Champlain Valley’s greatest music festivals. Now, we bring you an account of this year’s festival. Welcome to a weekend in the woods, Otis-style.

Day 1: Friday, September 11

It’s an unusually warm September afternoon, in the high 70s. The sun is smiling on Otis Mountain, as opening day dawns clear and blue. The core Otis crew and a cadre of volunteers are hustling to string last-minute lighting, clear out campsites, finalize stage setups, and haul trash and recycling bins into place.

The gates technically open at 2:00, but early birds start filtering in around noon. Attendees arrive by way of a hay bale truck. Two or three Otis crewmembers run the shuttle to and from the lower parking lots, ferrying attendees up Lobdell Lane. The crew announces when it’s time for the truck to get going or to let people off with a twangy cry of “bale up!” or “bale down!” respectively.

Bale up! Photo by Owen Ringwall

As last minute volunteers, we man the will-call booth for three hours. Armed with attendee bracelets, trash bags, maps, and lineup schedules, we greet this year’s Otis devotees and give them the overview of the weekend ahead.

More than a few attendees are sporting curious outfits. Hula-hoops and dreamcatchers dangle from backpacks, Technicolor sunglasses abound, and all manner of headgear can be found—from snapback caps and wide-brim felt hats, to beanies and fedoras.

Toting coolers, thirty-racks, tents, water jugs, and duffels, they leap off the truck and bound up the dirt path to the main gate. Once they’re checked in, most amble to Falls Brook Camp, the largest camping area.

Adventurous sorts might trek their gear to set up at Uphill or Summit Camps, which are deep into the woods on the actual mountain. Others might stake out at Cobble Hill camp near the entrance, close to Spruce Stage. Those looking for more privacy and space might head to Baxter Camp, located at the far back edge of the property line.

Map courtesy of OMGD.

Families are welcome at Otis. Photo by Shaun Ondak.

While twenty-somethings make up the majority of the guests, they are not the only ones who flock to Otis. In addition to the lot reserved for RVs and campers, the crew ensures there is quiet family camping separate from the larger, more raucous camping zones. Additionally, much of the daytime music is family-friendly, and more than a few toddlers can be found running around during the bluegrass sets. The original Otis Mountain Music Festival run by Jeff Allott drew mostly families, devoted bluegrass enthusiasts, and aging hippies. So, the roots of Otis as a family-safe retreat are still present at the Get Down.

Once 4:00 hits, the gate is swarmed with people checking in. Having sold roughly 1,400 pre-sale tickets, and reserving some others for day-of purchase, the crew expects roughly 2,000 people to attend this year. It will be their biggest year yet, up from last year’s 1,200 and year one’s 700.

It seems the wave will never end. Truckload after truckload of eager festival-goers arrive. At 5:00 another group of volunteers arrive to relieve us, and we quickly hit our campsite to grab a bite and stock our packs with beer for the night.

Along the way, we stop to peek at the art installations leading from the main stage to the lean-to.

Courtesy of OMGD.

Charlie Hudson is the artist behind the installation. For roughly two years, Hudson was the Creative Director of Burlington cotton and leather goods company Ediké Ayiti. Ediké is a socially conscious producer of ethically crafted totes and backpacks made in Haiti.

Between Ediké, a day job at Skinny Pancake, and attending UVM, Hudson painted when he could. Through the ski and snowboard community in Vermont, he also developed friendships with many of the people who run Otis, including Zach Allott and Quillan George.

After Hudson graduated in 2014, a few Otis team members set up shop in the Ediké office for two months leading up to the festival. This year, Allott called Hudson and asked him to produce some art for the festival.

“A couple ideas came to mind initially, but it wasn’t until Austin [Garrett] drove me out there three weeks before the festival where I decided what would work,” Hudson says. “He [Garrett] showed me this huge junk pile of old pieces of metal, fridge doors, car doors, oven doors, and I kinda freaked out.

“I’m a huge fan of rust and the pattern it makes on the metal. We loaded up Austin’s jeep with a ton of metal and headed back to Burlington where I painted the trees on each piece.”

“The first day that I ever went there it was quiet. The location really is pretty much in the middle of nowhere, which is so great. But just walking around the site when the festival isn’t happening is amazing,” Hudson says. “It’s just perfect, quiet, serene nature, which I love and which was the feel I wanted to capture in the pieces.”

“But then it’s also a ski mountain, a festival ground, and I’m pretty sure at one point a garbage dump. So there’s all these old, cool things just laying around the mountain, which maybe at one point were trash or ski equipment, but to me were all pretty interesting looking canvases,” he explains.

Hudson’s installation juxtaposes the paradox of sparse, uninhabited nature and imposing crowds. He intended for the metal to signify human presence, while the painted trees mingle seamlessly with the physical trees, incorporating the location’s existing ecology.

“The trees that you could see through the empty spaces of the installation were just as much a part of the installation to me as the actual paintings of trees,” he states.

“These man made objects were sitting at Otis Mountain for years and years, slowly rusting and turning back into nature. I wanted the whole project to blend in, yet stand out,” he claims.

Hudson’s pieces are subtle, simple, and almost imperceptible. These quiet qualities invite attendees to step back from the energy of the music and engage with Otis in a different way.

“With all the craziness that a festival brings with it, I wanted people to remember to look out into the trees, because especially at a place like Otis Mountain, the view is always going to be good,” he says.

Taking a break near the Otis sign. Photo by Malcom Watts.

The Main Stage by day. Courtesy OMGD.

The almighty Zero Gravity Cone Head. Photo by Pete Cirilli.

After admiring Hudson’s work, we trek to our campsite and fix a quick dinner. We’re eager to hit the stages and hear a selection of the festival’s almost 40 acts.

The Otis crew designs the schedule so that, theoretically, one could hear each set and there’s no risk of missing one band entirely. There are 45-minute breaks and one-hour breaks between sets at the Main and Spruce stages, respectively. While one band is playing on one stage, another group can sound check at the other. This allows attendees to bop to and from, sampling as many acts as they choose.

The first set we catch is Northhampton, MA funk-rock outfit Otter, at the Spruce Stage. Tucked away from the main stage in a forest thicket of Cobble Hill camp, the Spruce Stage is a small, cozy venue designed for smaller bands. Otter’s relaxed, undulating grooves are the ideal kick off to the night. Many people are head-nodding in small groups, conversing and easing into their first (or fourth) beers.

Next up on the main stage at 7:00 is Eastbound Jesus. A sextet from Greenwich, NY, they play a rollicking Northeast blend of bluegrass, Americana, and rock. With the sun setting and the banjo twanging, the crowd is energized and on their feet. Many Otis acts trade in some version of country or bluegrass, but Eastbound Jesus offers a unique tweak with harder, raspier vocals. “Keep On Hollerin” is one of their signatures, with a hip-shaking, foot-stomping beat and delicate harmonies.

Shortly after, Rockaway Beach, NY experimental duo Lewis Del Mar captivates the Spruce Stage. They weave pop, Latin American beats, reggaeton, and R&B to create a textured sound that is diverse and hard to define, like a rich mixed media painting. “Memories” is evocative, sexy, and layered. Percussion drops in and out, while rapid drumming and falsetto vocals compel the soul.

Headlining the stage at 8:45 are the neon-spandex wearing Burlington pop boys Madaila. They deliver their usual irresistible brand of retro pop and electro dance grooves. Front man vocalist Mark Daly appears like a modern reincarnation of Prince, wiggling and crooning his way around the stage. The band’s rendition of Whitney Houston’s “How Will I Know” whips the crowd into an 80s love frenzy, while their original numbers “Give Me All Your Love” and “International Lover” appeal to the Burlington fans in attendance.

Madaila goes Technicolor. Photo by Pete Cirilli.

A bit out of breath from these initial sets, we decide it’s time for a respite in the woods. At Otis, some of the most special moments happen away from the crowds.

Walking along the path back to Falls Brook Camp, we stumble across “Fort Twenty.” Constructed out of leaning pine limbs, “Fort Twenty” is a tiny, teepee-like venue designed for intimate and semi-spontaneous acoustic shows.

Fort Twenty by day. Courtesy OMGD.

The stage is built on tires and wood planks, and the interior only has room for ten or so listeners. Here, we find The North End Honeys, a new country, honky-tonk group who got their start busking on Church Street in Burlington.

In a space as sparse and natural as Fort Twenty, the Honeys forgo the screaming honky-tonk and instead slow things down, playing quiet numbers. Their original tune “Church Street Salvation” is a cheeky ode to one-night stands and bar crawls.

But their performance of Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me” is, quite simply, stunning. Songstress Hannah Fair captures King’s original grace and gives a tender, affecting, and wistful performance. Fiddler Tucker Hanson—also of Reverend Ben Donovan & the Congregation— lends his talented hand and keeps things just country enough.

Smitten with the hidden magic of Fort Twenty, we vow to return later to see who pops in. We wander the woods for a bit, exploring the light displays and taking the long loop around the campgrounds. Some attendees have gathered around fires, taking a break from the festivities. At Otis, you can be as involved or isolated as you wish.

The Lean-To is a popular spot for keeping warm by the fire and swapping stories. A wooden structure swaddled in lights, it is bedecked in feathers and flowers, with bottle wind-chimes dangling from its beams. Off-the-cuff jam sessions take place when someone wanders in with a banjo or a fiddle, and games of stump often crop up outside. Sausages simmer over the grill and whiskey is passed. Hay bales and low benches provide seating and space for conversation.

The Lean-To at night as seen from uphill. Photo by Shaun Ondak.

“The Bog” at night. Photo by Pete Cirilli.

Back on the main stage, Wild Adriatic is headlining. The Saratoga Springs rock group performed an impressive 175 acts in 2014, including major gatherings like SXSW and moe.down. Although they are a three man band, their stompy, bluesy, thoroughly rock and roll cuts recall the larger-than-life sound of 70s era supergroups.

We catch a few songs before descending into “The Bog,” a bowl-shaped DJ pit beyond the Lean-To. Cradled against a sharp cliff —used for ice climbing in winter— this spot is ideal for isolating the pulsing sounds of late-night electronica from the music on the other stages. It’s also just a great place to throw a party.

DJ Steal Wool opens his 11:30 set, and things soon turn old school. One hit wonders like Matthew Wilder’s “Break My Stride” and iconic tracks like “Thriller” are remixed with modern beats. The crowd approves. Plastic bottles are passed and glow bracelets light up the night. It’s easy to forget you’re deep in the Adirondacks, not an underground club in Montreal.

Just before 1:00 am, we feel our stamina slipping away and decide to call it a night (although the tunes last until much later.) We spy some folks packing into their tents, too, but— judging from the sounds of laughter and howling that wake us intermittently throughout the night and into the early hours of Saturday morning— it’s plausible that some people simply don’t go to bed. We drift in and out of sleep, restless for the day ahead.

Day 2: Saturday, September 12

The music begins at 11:00 am on the Spruce Stage, but we need to refuel before hitting the ground running. After a hearty breakfast of beer-batter pancakes— upgraded with Nutella and bananas— we pack a road beer and amble down the dirt road to dip in the Bouquet River.

We’re not the only ones with this idea. About twenty people are lazing by the riverbank, hoping to cool off— and perhaps atone for last night’s antics. The water is chilly from mountain runoff, and fairly shallow. A few brave souls jump from the bridge above, or cast out from the rope swing underneath. Others merely swim and splash around. Once we jump in and feel that first brace of cold, we are certainly awake.

River swim. Photo by Michael Doordan.

We kick off our music with The Tenderbellies at 2:15 down in The Bog. The Tenderbellies are well known to Nectar’s Bluegrass Thursdays crowd. Their set today is quiet, acoustic, and rustic. Folks sit on the ground or on hay bales at the back, silently listening.

Many songs are instrumental, but vocalist Claire Sammut shines with “Angel From Montgomery,” originally penned by John Prine and popularized by Bonnie Rait. Sammut’s voice is delicate and pure, but strong and lifting.

The Tenderbellies play some original tunes, but after repeated pleas for a rendition of Neil Young’s “Old Man,” the band finally obliges.

This is The Tenderbellies’ third year at Otis, and speaking with the band later, it’s clear that they are drawn to personal, humble venues that encourage a closer audience connection.

Guitarist Chris Page says the appeal of playing at Otis is the gratitude that bands receive. “The people here are incredibly gracious no matter what style we’re playing with or crowd we’re playing to,” he says. “No matter what we do, people walk away thanking us. That’s a special thing to be thanked, instead of just paid.”

Stand-up bassist Luke Hausermann adds, “it’s also a cool thing for musicians, I think. Last year we met some musicians that we’ve linked up with and played with through Otis.”

The band has released an EP of bluegrass covers called “The Songs We Picked,” but says they want to branch out from the genre.

“We want to start pushing for ‘soul grass,’” Hausermann laughs.

Page says, “we want to start bringing in the gospel music and the harmonies. And in a bluesy ways, bluegrass is fun, but I think people are really drawn to when we do things that are more dulcet and maybe a little slinkier.”

Suitcase Junket. Photo by Malcom Watts.

Over on the Spruce Stage, one-man show Suitcase Junket (Matt Lorenz) is performing. There are few ways to describe him other than the older meaning of the term “strange.” His music is otherworldly, odd, and entirely mesmerizing. Offbeat instruments of his own creation include “a resurrected dumpster-diamond guitar, an old oversized suitcase, a hi-hat, a gas-can baby-shoe foot-drum, a cookpot-soupcan-tambourine foot-drum, a circular-saw-blade bell and a box of bones and silverware that operate much like a hi-hat.” Lorenz’s ethereal voice beautifully contrasts the stomp and sway of his instruments. He arranges his songs in such a way that he truly sounds like a five-person band. The intense, gravelly “Earth Apple” is a crowd favorite.

American roots orchestra Dustbowl Revival takes the main state at 5:15. This California based eight-member band features all manner of instruments. Besides the usual guitar, bass, and drums, they play washboard, mandolin, tambourine, fiddle, trumpet, trombone, and even ukulele. Their sound is a hodgepodge of swing, blues, jazz, bluegrass, soul, and funk. In essence, the melting pot of American music.

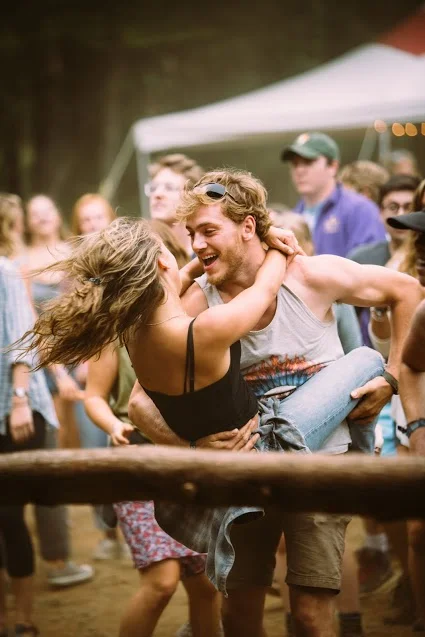

Dancing by the main stage. Photo by Pete Cirilli.

Their cover of Tom Petty’s “Last Dance With Mary Jane” is a crowd pleaser. It’s a fitting end-of-the-season song that captures the wistful melancholy of another summer gone by.

Dustbowl Revival certainly has stage presence, but they forgo that for an impromptu encore jaunt into the crowd to clap and sing along.

After all the foot stomping, it’s time for a snack break, so we head over to one of the food trucks. Otis brings in local vendors such as Miso Hungry ramen, Clay Hearthflatbread pizzas, and Pingala, a vegan eatery from Burlington.

Rain has been threatening all day, and we have been cautiously watching the changing clouds. As Adirondack weather is wont to do, it can shift from partly sunny and humid to cloudy and chilly in an instant. As we stand in line for our pizza, the skies finally unleash.

Rain has been threatening all day, and we have been cautiously watching the changing clouds. As Adirondack weather is wont to do, it can shift from partly sunny and humid to cloudy and chilly in an instant. As we stand in line for our pizza, the skies finally unleash.

The rain does not relent for the rest of the night. Yet, looking around, it seems no one is deterred. The magic of Otis is that the rain almost inspires people to sing louder, dance faster, and go harder.

Northampton, MA sextet Bella’s Bartok relishes in the rain on the Main Stage at 7:00. A sort of Eastern European, Balkan-inspired rockabilly circus group, they are quite unlike any other band. They play Old World tunes with a modern, theatrical twist.

Next, soul-funk outfit Smooth Antics grooves up the Spruce Stage at 8:00. For a band that first played Otis on a two-week notice whim, Smooth Antics sure has made up for lost time. In just two years they have solidified a core lineup, recorded a full-length album, played nearly every Burlington venue, and launched a larger Northeast tour.

Back in summer of 2013, Drummer Jake Mayers was working with Quillan George to book bluegrass bands for the original festival. Mayers recalls George calling him two weeks before the festival asking him to play with his band, which had gone on summer hiatus.

“I was like ‘I don’t know if we’re ready yet, we don’t even have a name.’ But we did it. We came up with a set list in the RV,” Mayers laughs.

Smooth Antics drummer Jake Mayers at Otis 2014.

They performed under the name “Jake Mayers Band” on the Spruce Stage at the first Otis. Mayers says that stage is, “super intimate, which is a crucial part of our performance.”

A few weeks later, with a newly crowned name, Smooth Antics took off. “We got a residency at Nectars for 5 weeks and from there we were basically able to tour and take it on the road,” Mayers says.

In 2014, George invited the gang back for a nighttime set on the main stage. In contrast to the humble vibe of year one, the second performance included five dancers and a three-piece horn set.

Bassist and vocalist Mike Dondero believes that Otis is a reunion of sorts for the band. “We all said regardless of what we have planned or what’s going on in the future, we’ve got to do Otis,” he says.

Smooth Antics vocalist Steph Heaghney. Photo by Casey Joseph.

Indeed, at this years’ set, Heaghney called out to the crowd and exclaimed, “this is our anniversary!”

Dondero’s favorite aspect of playing at Otis is the community of musicians. “It’s pretty much the whole Burlington music scene and the bands who also come to Burlington and gig there. It’s cool to see everyone progressing year by year.”

Mayers agrees. “There’s an Otis thread, and you’re able to help each other out. Playing here is just magical. It’s unlike anything else,” he says, adding, “It’s almost indescribable.”

Now a seven-member group, Smooth Antics has perfected its self-described genre of “booty-shakin soul-hop.” Their priority is to first establish a danceable groove, then layer soulful melodies with instrumental elements of hip-hop, R&B, and funk. On stage, Heaghney is the star of the show. As a trained dancer, she knows how to command a stage and incorporate the physical body into the metaphorical body of the songs. Smooth Antic’s Spruce Stage performance this night delivers, and also holds a special resonance as the place where they began.

After taking a break and attempting to dry off, we hit the main stage at 10:30 to witness resident Vermont punk rock boys, Rough Francis, do what they do best. These guys know how to screech and shred, and they waste no time. Lead singer Bobby Hackney Jr. lets out a hyena-like scream and the guitars come crashing in. The crowd had been taking refuge from the rain under tents, but once they hear that guttural cry, they quite literally run down the hill en masse toward the stage. A raging mosh pit forms almost immediately.

Rough Francis frontman, Boby Hackney Jr.. Photo by Casey Joseph.

Rough Francis has a hard edge— that part is undeniable. But don’t mistake them for a band of ruffians who play loud music for the sake of playing loud music. They are talented and thoughtful musicians with tight arrangements, and they rage to get their point across. Tonight, they play their standard garage punk-rock, but with a modern message, performing several songs addressing recent police brutality and racial tension. It’s a powerful moment when Hackney Jr. calls out to the crowd, addressing the Black Lives Matter movement, and is met with resounding cheers of support and solidarity.

Grundlefunk fall tour schedule.

Next, Grundlefunk jams on the Spruce Stage with an 11:45 set. Grundlefunk plays, well, funk. Specifically “the dirtiest funk around”—or at least, that’s how they got their name.

“The name started out as a joke made by our drummer’s old roommate,” trumpet player and percussionist Glen Wallace explains, “After a few gigs, we discussed changing it, but could never find another name that felt right, so it just sort of stuck.”

Grundlefunk’s first Otis experience in 2013 came after just being together for six months, and was invited back for both subsequent festivals. Wallace says that Otis is, “a great, safe place to try new material in addition to our work horse tunes.”

The band has gathered a steady Burlington following with Nectars and Radio Bean shows, and currently has an EP in the works. Grundlefunk’s self-described “jazzy casserole fresh from the funk oven” is indeed jazzy. With emphasis on keys and saxophone, they steer away from the psychedelic, spacey end of funk. Vocalist and front-woman Nicole D’Elisa —who also leads Nico Suave and the Bodacious Supreme—has a deep voice that recalls soul songstresses of the 60s and 70s.

As the rain continues to soak Otis Mountain, late night sets continue on both stages, and The Bog rages until past 3:00 am. Undeterred by the downpour, determined attendees strap on more rain gear and ride out the weekend with panache… and PBR.

“The Bog” lights up at night. Photo by Shaun Ondak.

Day 3: Sunday, September 13

Unfortunately, it’s time to pack up and leave this mountain retreat. Considering the all-night antics, it’s surprising that most campsites are cleared out by 10:00 am. Perhaps the ceaseless rain finally got the best of people.

We are working the merchandise booth and helping the team break down the festival, so we linger until 2:00 pm. By this time, the crew is nearly done collecting trash and removing equipment.

But, the work at Otis never ends. Within a few days, the crew will be recapping the highs and lows of the festival and begin work for next year. This is not to say that Otis is a Sisyphean task. Far from it. It is also too cliché to simply call Otis a “labor of love.”

Otis is a word with connotations varied and deep. It is a spirit, an ethos, a mountain, a festival, a community, a group of friends, a weekend, an escape, and a canvas for creativity and memory-making.

Otis Mountain is enchanting not for the grandness of its natural beauty or the celebrity of its musicians—though both exist. Rather, it is intoxicating in its ability to affect its visitors.

Otis sinks into the skin and imprints on the mind. It is something that can be experienced, but not replicated. In a world often defined by transient, incomplete, or artificial interactions, Otis is a salve—a balm for those who crave something paradoxically unique and universal.

The only way to discover its charms is to see and hear it for yourself. We’ll see you next year.

For information on concerts and special events throughout the year, subscribe to an email list here: http://www.otismountain.com/contact/. Also, keep in touch with Otis on Facebook or Instagram.