Otis Mountain Get Down: Little Mountain, Big Heart // Part 1

------

Update. You can now read part one and part two under my articles tab!

------

words // Liz Cantrell || photos // Jeff Allott & Otis Mountain Get Down

To find it, you almost have to know it’s there. Roaming State Highway 9N, you could easily cruise by Lobdell Lane without looking twice. Yet, tucked in a low-elevation pocket of the Northern Adirondacks, in the southern portion of New York’s Champlain Valley, there exists a place where music mingles in the pine trees, where campfire smoke curls high over a circle of friends.

On the second weekend of September, turning down that dirt lane will deliver you to a three-day music festival that defies stereotypes and exceeds expectations. You’ve arrived at Otis Mountain Get Down, and you’re going to have a weekend for the ages.

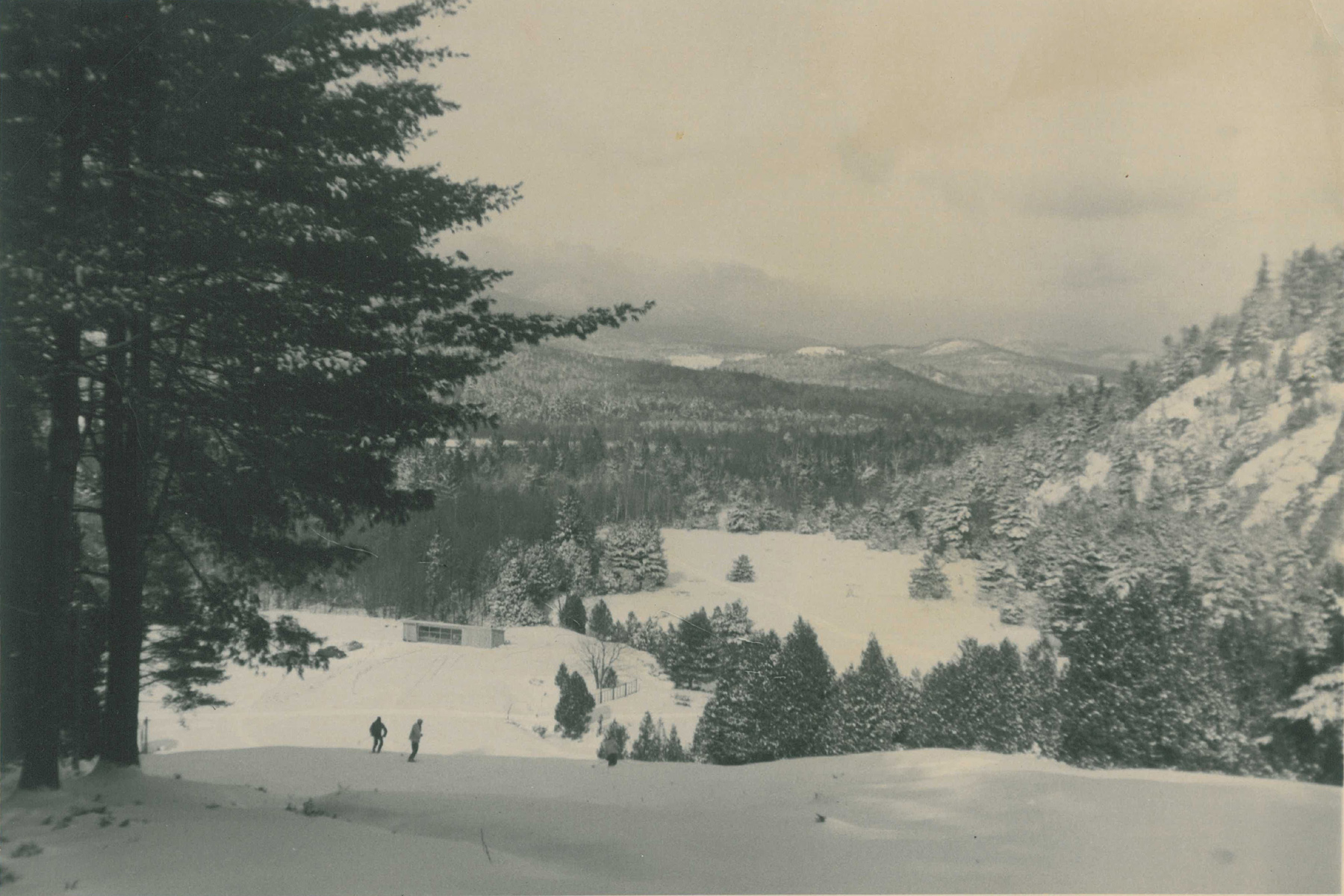

Located in Elizabethtown, NY—population 1,163 as of the 2010 U.S. census[1]—Otis Mountain is in the thick of Adirondack country. But, with a gradual approach to the clearing and a gentle ski-hill slope rising above the festival grounds, the terrain is welcoming, not imposing.

Terrain surrounding Elizabethtown, NY

OMGD features over thirty acts in a variety of genres, from whiskey-infused bluegrass and old-time country, to righteous soul and funk, to modern hip-hop and electro. The goal is not to showcase major national bands or attract corporate sponsorship. Standing out from— and in many ways against— the “festival culture” that defines well-known events like Coachella and Bonnaroo, OMGD instead offers an intimate, interactive, and affordable weekend experience in the woods.

In part one of a two article series, Offprint takes a look at who and what have made Otis what it is today. From its days as a small community ski hill, to a six-year stint as a summer bluegrass haven, to a 21st Century music festival revival, Otis Mountain has a story to tell.

The Ski Years

The life of Otis Mountain has been one of ups and downs, with alternating years of high success and years of dim closures. Only in the last twenty of its eighty-year history has it operated continuously.

Before its transition into a public-use area, the mountain sat on private farmland owned by the Lobdell family of Elizabethtown. Starting in January 1940, the Elizabethtown Ski Club leased the property in order to operate a small ski program. The club stayed in business sporadically until 1959. Not much documentation of these early years exists.

View from the top of Otis Mountain ski hill. Courtesy Jeff Allott.

Jeremy Davis, founder of the New England Lost Ski Areas Project and noted ski historian, has researched Otis Mountain extensively. He speculates as skiing became a more popular form of recreation, bigger mountains began to attract customers, so small community hills like Otis lost support.

Otis lay dormant until local volunteers formed the new Otis Mountain Ski Corporation, opening the hill in January 1965. Yet within five years, the corporation was unable to pay operations costs. In 1970 it asked locals Jane and Herb Hildebrandt to purchase the property.

Getting in line at Otis ski hill. Courtesy of Jeff Allott.

The Hildebrandts spent two years renovating and recouping money from the acquisition and repairs. The couple added a new T bar to the lift, made updates to the facilities, and added free Wednesday night skiing. The Hildebrandts kept Otis running from 1972-1979 as an affordable location for families to ski.

It was during these years that Elizabethtown native Jeff Allott became acquainted with the mountain, and with the Hildebrandts.

“I literally grew up skiing there. I was the ski patroller at one time, I worked the hot dog stand, I did every job,” he remembers. “It was a vital thing, back when skiing was popular and a lot of small towns had their own ski hills. All the school ski hills would come to Otis instead of Whiteface, which was too big and expensive.”

In the season of 1979-80, there was much anticipation that the Winter Olympics in nearby Lake Placid would draw attention and bring business to Otis. But, Davis notes, “that season and the following were terrible for snowfall, it was very dry winter so the Hildebrandts weren’t able to open. They tried to get the area going again in ‘82, and there wasn’t enough snow either so that was the end of that operation.”

Young skier at Otis Mountain. Courtesy of Jeff Allott.

By this time Allott had graduated from high school and traveled the country as a ski mechanic. But he frequently returned to the mountain he grew up on. “Every year when I’d come back I’d say to Jane, ‘one day when I get my act together I’m gonna buy that and we’ll get it running again.’”

In 1994, he finally did. Having earned a degree in mechanical engineering, he started a composite materials company in Albany. When a fire took out the entire facility, he took the opportunity to relocate to Westport, about nine miles from Elizabethtown.

Cover of "Lost Ski Areas of the Northern Adirondacks" by Jeremy Davis

“That same winter of ‘94 I got a call from Jane saying ‘you have to do something someone is trying to buy the property!’” Allott recalls.

Allott was able to gather two friends and get the money together in the summer of 1995. The mountain now operates with a simple rope tow. “It’s been running ever since, and we’re coming up on our 20th year,” he says, with amazement.

Such a story of revival is quite unusual, Davis notes. “It’s a rare case that you have an area that’s been closed so long that opens on some kind of a level,” he explains.

In fact, of fifty-four former ski areas of the Northern Adirondacks that Davis has documented, only seven have reopened. Otis, then, is quite the exception.

A Bluegrass Addition

Allott continued to open Otis each winter. He remembers that early in the summer of 2002, someone mused that the property would be an ideal site for a music festival.

“Surprisingly four or five of my buddies said ‘yeah I’ll help you with that.’ Literally that summer we threw a stage together, ran power up there, and focused on mountain music, just bluegrass and family friendly music,” he says.

The theme stuck. The Otis Mountain Music Festival, as it was known, ran for six years until 2008. At the time, Allott says, almost no one but locals and dyed-in-the-wool bluegrass enthusiasts attended. “I would literally cruise the parking lot and never see Vermont plates, it just could not break through to Vermont,” he laments.

The main stage. Courtesy of Otis Mountain Get Down.

Growing weary of the effort required to put on the festival, Allott and company took a hiatus for one year, then two, then three, and ultimately gave up altogether. But the ski hill lived on each winter.

A Festival Revived

It seems only fitting that a property passed from friend to friend, from person to person in the community, would ultimately end up repurposed in the hands of those who enjoyed it for so many years.

Allot raised his family in and around Westport and Elizabethtown. “The ski area had continued to grow and my kids all grew up skiing there. We went every weekend,” he remembers.

His oldest son, Zach, attended Champlain College in Burlington, VT and would frequently bring friends home to enjoy skiing and other activities at Otis. Many of those people— including Austin Garrett, Colby Sears, and Quillan George—would ultimately help him resurrect the summer festival aspect of Otis.

During Zach Allott’s college years at Champlain, he lived in a Burlington apartment— affectionately dubbed “The Range” — that housed a group of about fifteen rotating people, generally seven at a time.

“The Range,” was, according to Sears, “a big spot to go hang out, and that’s where the friendships really took off.”

“There was a bar, mini ramp, and bands just about every weekend. Through hosting all of these acts, we had a lot of connections in Burlington's live music scene,” George describes.

In the early summer of 2013, some of the group went to New York to go cliff jumping and stopped at Otis. George recalls looking at the old bluegrass stage at the bottom of the ski hill, and saying, "Why don't we get some bands over here?"

Fun around the fire at Otis Mountain Get Down. Courtesy photo.

Plans began the next day. “I started texting friends in bands with the idea, and people were interested. We reached out to some more buddies that we thought would want to get involved, and started making the festival happen,” George recalls.

The initial idea was to host ten bands and reach out to immediate friends, bringing in about 100-200 people.

“As soon as we put the festival online, it blew up,” George says, “There was a rush of locals that had attended the bluegrass festival in the past that were incredibly excited to see the return of music to Otis Mountain, as well as a bunch of friends and friends of friends.”

It quickly became apparent, however, that the undertaking would be much more work than expected.

“When we first started we didn’t really have a plan,” Zach Allott admits.

George adds, “We had planned a date about a month and a half away from when we first had the idea, and quickly realized we wanted to do this right and needed more time, which is how we fell on the date in early September.”

With the core group of “The Range,” plus help from Jeff Allott and additional volunteers, the 2013 inaugural OMGD was a hit. What began as an idea to bring a group of friends and a few bands together turned into a 25 act festival with over 750 attendees, according to George.

The gang’s biggest lesson from the first year was logistics. “We were organized, but only as organized as a group of 21 to 22 year olds with no experience in putting on a festival could be,” George says.

“It’s pretty humbling, and realistically we are responsible for all these people so that kind of made us grow up fast,” Zach Allott says. “In some ways,” he adds, with a laugh.

This year, a group of thirteen Otis veterans incorporated as a small business in the form of a cooperative LLC. This structure allows them to retain earnings from year to year and for all members to have equal say.

How The Get Down Gets Done

With a formal business structure, OMGD now exists as a fully bootstrapped organization. And its members work hard all year to make each September a success.

Sears says, “We go all year, sitting in group meetings. We take a week off so right after the festival, then we sit down and plan all over again.”

The Monday after the festival, the group sorts through video footage and photos to produce a recap video and begin planning a media calendar. Next on the list is “a thank you, follow up note to everyone involved, artists, security, production, etc, what they thought worked well, and how they thought we could improve for the next year,” George says, “This feedback has been a big reason why we've been able to continue to grow and improve each year.”

George is the Talent Buyer as well as the Marketing Director and Music Production Director. He is responsible for booking, scheduling, and coordinating all musical acts, as well as coordinating sound and lighting. He also directs all marketing efforts.

“I try to have at least half of the lineup confirmed by 6 months out, and all of it complete by three months out,” he says, “Once we hit four months is when we really start to push everything publicly. Before that a lot of what is happening is all internal.”

Bands are selected in a number of ways. Some artists send samples via email and social media. Otis team members also nominate artists they’d like to play at the festival. George also scouts talent through connections with Burlington music venues Signal Kitchen and ArtsRiot, as well as other festivals throughout the country.

“The main idea behind how we select our line up is that we never book bands based on popularity. We choose artists based on quality, diversity, and spirit,” George states.

Late night set at Otis Mountain Get Down. Courtesy photo.

Once most artists have been locked in, much of the site prep and contract work begins. Garrett and Sears are facilities coordinators. Their tasks include negotiating terms for food and merchandise vendors, organizing and scheduling volunteers, drafting contracts, and coordinating the legal and creative elements.

Sears explains, “On the back end it’s working with insurance to make sure we’re adequately covered. What I try to work on is establish and build budgets.”

When summer dawns and the festival is only three months away, the crew has someone on site almost every weekend.

“The winters are pretty brutal on the stages and structures, so there is a lot of rebuilding and clearing out more camping for the growing number of attendees,” Garrett explains.

The group does all the building and maintenance on site and by hand. Jeff Allott is always around, linking more power to stages, mowing the grounds, and offering the wisdom of experience.

One month before the gates open, the crew pushes a marketing blitz. Posters and promotional materials are sent out, social media posts occur almost daily, and radio and local press are contacted.

One week from the festival, the team is on site full time. While there are formal positions in the collaborative's legal structure, the roles are loose, especially during those last few days before the crowd arrives. This horizontal structure is essential to the Otis ethos.

“No one does more work than anyone else. Some people are doers on the ground, some people are coordinators,” Sears says. “The only reason we have titles is because we were nominated amongst the group, and some of us have different backgrounds that make the titles more applicable.”

More Than A Mountain

With only one week left until this year’s festival opens, the crew is working to finish the remaining elements. But, they are also reflecting on what makes Otis meaningful to them and to the Elizabethtown community.

“What we wanted to do from the beginning was provide a totally different festival environment for people,” Sears says. “At the grandiose festivals it’s $200 a ticket. This is not about that. It’s about the music, and about friends."

Garrett agrees. “Otis has become something so much more than just a mountain or a festival to me. I love being able to take people there who have never been and show them all of the cool stuff scattered around the grounds,” he explains.

For George, the point of the festival is, “to expose people to something new. There is nothing I love more than hearing someone say ‘I've never heard of any of these bands.’”

In terms of the crowd, Jeff Allott has been surprised to see a parking lot full of Vermont cars, unlike his festival days. “In 2013 was 90% Vermont plates and 10% local plates, the dynamic had completely flipped. I was like ‘damn!’” he laughs.

By bringing in outside tourism from Vermont and other states, OMGD has become a small economic jolt to the community of Elizabethtown. “It’s more apparent every year it’s more than a festival,” Zach Allott says. “Last year they were selling out of everything at the stores the week of, so it’s become a viable entity for the town.”

Sears says he appreciates some of the smaller moments at Otis. “Some of my favorite times are seriously just driving the hay bale truck up and down. I have driven that truck for like 12 hours a day,” he remembers. “Everybody is so stoked on that ride up the hill. That to me says we’re doing something here, people are happy and there’s this safe environment to have fun. It comes full circle.”

Lights and a packed crowd at OMGD. Courtesy photo.

Garrett attributes a lot of the festival’s success to the attitude of the attendees. “Otis attracts such a great crowd, I can't tell you how satisfying it is on Sunday to walk through the camp sites and see that almost everyone has cleaned up after themselves. That's what it's all about,” he states.

To Jeff Allott, Otis also represents a generational passing of the torch. “It was really something to see it brought to life again through my son,” he says.

---

Otis Mountain is a storied property that has been given new life. The “little ski hill that could” has survived snow-starved winters, closures, changing hands, and more than a few weekends of boot-stomping music and mayhem. With the third annual Otis Mountain Get Down just one week away, the tradition and spirit of Otis lives on.

As this article goes live, Offprint heads into the woods to meet the crew and experience life at the festival. Check back in a few weeks for a recap of the music, art, and people at OMGD 2015. To buy tickets to the festival, which runs Friday September 11-Sunday September 13, visit http://www.otismountain.com/tickets/

For more information on the history of Otis Mountain and the Northern Adirondack region, visit the New England Lost Ski Areas Project (www.nelsap.org)

The Full Otis Crew

- Zach Allott, President

- Pat Dodge, Product/Merchandise

- Ryan Forde, Designer

- Joe Fortugno, Treasurer

- Colin Frost, Volunteer Coordinator

- Leanne Galletly, Secretary

- Austin Garrett, Facilities Coordinator

- Quillan George, Talent Buyer, Music Production Director, Marketing Director

- Casey Joseph, Social Media Manager

- Evan Litsios, PR / Copywriting

- Tommy Lyga, PR

- Colby Sears, Facilities Coordinator

- Bobby Sheridan, On-site operations

- Brian Somers, Vice President

- George Watts, Media Coordinator

[1] http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml

Find the full Offprint website and article here! http://www.offprintmag.com/culture/otis-mountain-get-little-mountain-big-heart-part-1/