It's Been A While

I took an unplanned two year hiatus from blogging because, well, I was busy, as we all are. Like many people, the pandemic has caused me to rethink the "busyness" of my life and whether being “busy” had value. Below are some thoughts I had in the first several weeks of the pandemic, which were dark and uncertain and long. I now have much more optimism—though there is a long road ahead, I am astounded by the city’s resilience, community, and character.

Over the next weeks and months, I hope to return to sharing stories here, from where I left off in 2018 and where I am now.

In the early weeks of March and April, I looked back on all the things I used to fixate on, the notes in my phone with books to read and places to visit and things to look up, the endless errands, the to-do lists I crossed-off, my weekend routine, workout classes—all the carefully regimented hours, days, and weeks of my "life."

Theoretically, I have infinite time now. All roadblocks—commuting, number of hours I must be in the office, after-work events, appointments—have been eliminated. And it turns out, I needed those roadblocks. I feel lost without them. And really, what was I "getting done?"

Was it a byproduct of living in a crowded city, or a corporate rat race, or pure everyday necessity, or some combination. The lack of things "to do" is forcing me to turn my attention to my own choices and what I want my life to look like when this is over.

I read this quote one day in April, and it has been with me since:

"Unfortunately, you were given a structure — a fake one — growing up and you were told that following the structure makes you a good person This is unfortunate because your structure has been decimated recently. Please know that that’s ok. You were already a good person"

I considered myself a disciplined, productive person. I prided myself on being someone who "got things done." But the first few weeks of the pandemic cracked something inside me. I felt adrift, useless, restless, scattered. Who was I without those structures that held me together? No one, I feared.

At the beginning of the year I made a list of things I wanted to do "more" and "less" of. I wrote them in my notebook on a clean page, a line down the middle dividing the things I would move toward or leave behind.

More:

baking

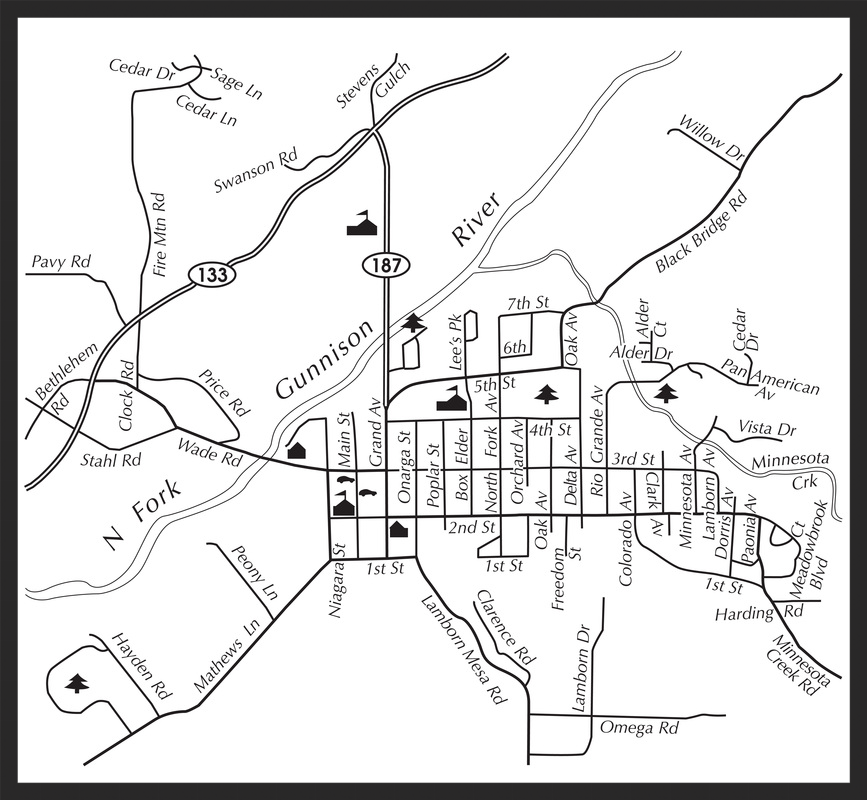

walking the city

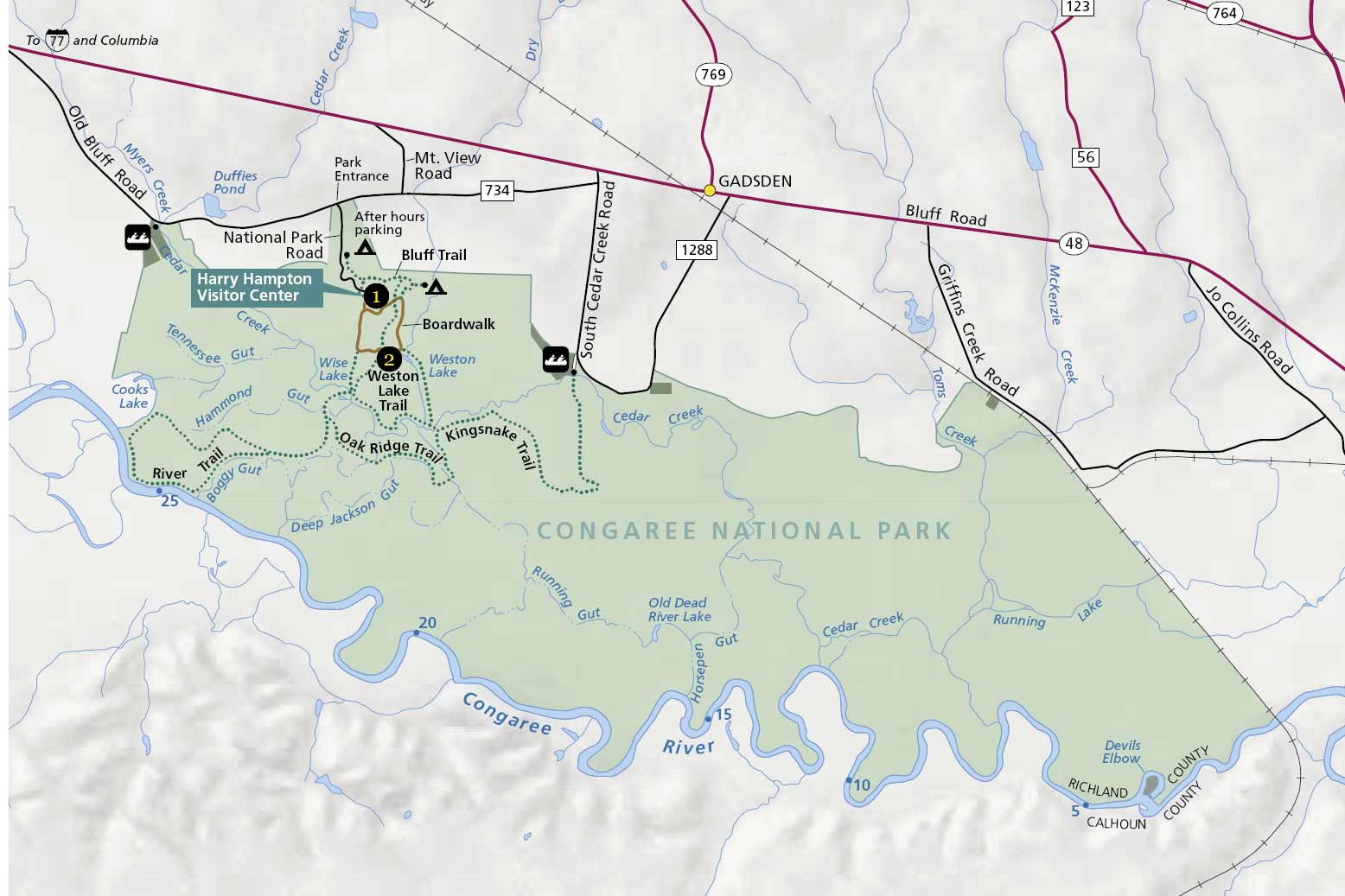

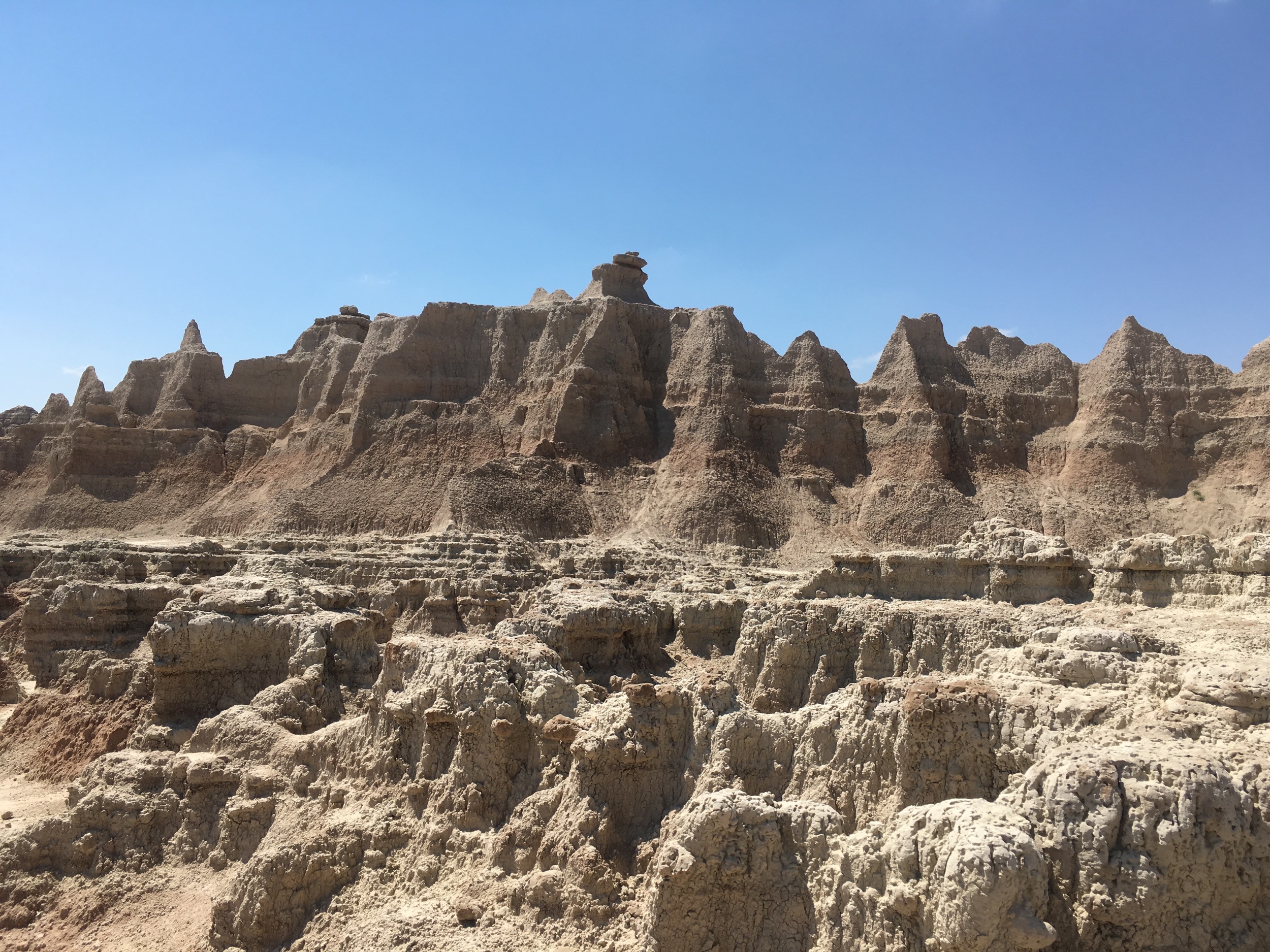

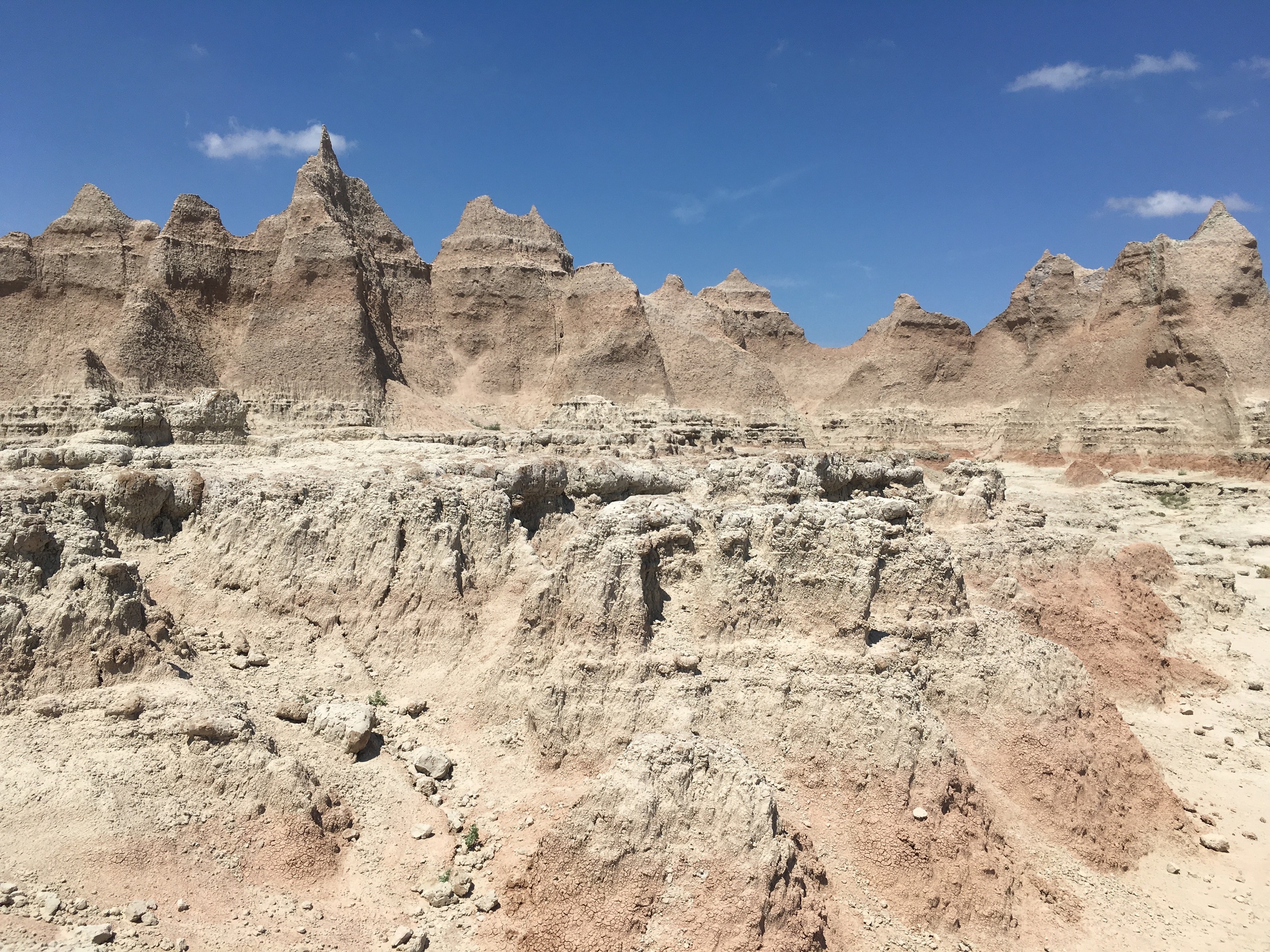

hiking/camping

trust (in people and the universe)

Less

screen time

rush to judgment

projecting or forecasting bad outcomes

comparisons

Looking back at the list, I have to laugh. Early in lockdown, I did all things I wanted to let go of: I was on my phone or computer constantly, looking for updates on the crisis, reading article after article, or turning to distractions; I panicked or jumped to conclusions easily.

Oddly, I have done two things from my "more" list that I didn’t know could bring peace and clarity. Like everyone else, I’ve been baking (biscuits, scones, pancakes, waffles, banana bread, apple crisp.) And I have been walking, oh have I been walking: two or three times a week, I’ll walk about 80 blocks: from the mid 50s up the east side of Central Park to the mid 80s, cut into the middle, wander around the reservoir or the Ramble or the Great Lawn, and walk back. Or I’ll do a shorter line along the East River promenade, watching the tugboats and now, the summer jet skiers.

I used to think it was helpful, even necessary, to delineate things I should and should not do. I loved lists. I thought they brought me clarity. Now I look at those two tiny columns I scrawled in January, my brain thinking I had it all figured out. How very wrong I was. I see how the lists have collapsed into one another, how the order and hierarchy of things have changed. I was hell-bent on self-actualizing, on optimizing my time and thoughts. Now, there is no "more" and "less," just enough.

When I look at this list, the big one that, sometimes, still eludes me is "trust," in others, and in the universe. It might be the most important thing I do all year.